Edward John Dent, how a chronometer maker made the turret clock of Big Ben, part 1.

This blog is based again on a lecture that I have held in the shop in May 2016.

This blog is based again on a lecture that I have held in the shop in May 2016.

About six years ago I have read a book written by Vaudrey Mercer based on letters to and from Edward John Dent which tells several stories in his private and professional life. For instance his partnership with John Arnold, several inventions and patents, private life and his working relation with G.B. Airy the astronomer Royal. Through these letter we do not only learn about these matters but also on 19thC life and customs. One of the stories that might relate to lot of people (always a good qualification for a lecture) is the story about the making of the Great clock for the houses of parliament, commonly known as Big Ben. There are even doorbells with the famous Westminster Chimes, so I thought this would be story that people could refer to.

First we need to introduce the main characters.

First we need to introduce the main characters.

Edward John Dent was born in London in 1790. In 1807 he became apprentice to Edward Gauding and probably also learned some clock making from his older nephew Richard Rippon. From 1814 on he slowly but steadily builds his reputation as a very good clock maker.

For instance; he builds a regulator for the Admiralty in 1814. He probably was working for the renowned chronometer makers at this time and less under his own name. Somewhere between 1822 and 1824 he becomes one of the go-to repairmen of the Royal Observatory.

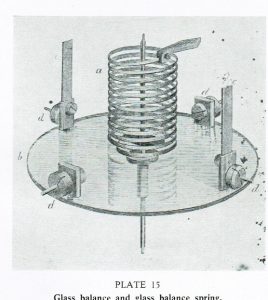

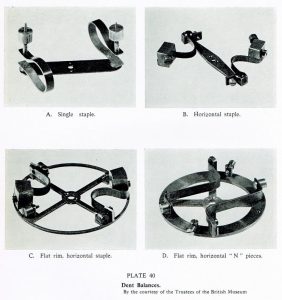

He even wins the annual chronometer competition in 1829. There are several patents from him and he did a lot of experiments with balance types. He even invented a glass balance with a glass balance spring which did not have any influences from temperature changes. From 1830 until 1840 he has a partnership with chronometer legend John Arnold. And finally we know that Dent had 3 shops in London in 1847.

(* Jonathan D. Betts, Encyclopaedia Britannica online)

George B. Airy was born in 1801. He graduated in 1823 from Trinity College Cambridge, became professor in Mathematics in 1826. He became professor in Astronomy in 1828 and director of the Cambridge Observatory. In 1835 aged 33 he became Astronomer Royal, the director of the Greenwich Observatory. But besides Astronomy Airy was interested in other things among which horology. He wrote for instance a book on wheels and gears. And later he even invented an escapement.

George B. Airy was born in 1801. He graduated in 1823 from Trinity College Cambridge, became professor in Mathematics in 1826. He became professor in Astronomy in 1828 and director of the Cambridge Observatory. In 1835 aged 33 he became Astronomer Royal, the director of the Greenwich Observatory. But besides Astronomy Airy was interested in other things among which horology. He wrote for instance a book on wheels and gears. And later he even invented an escapement.

Dent and Airy were to know each other for years and worked together closely. One would think that there would some equality or friendship after all these years. But this was not the case. Airy was higher up on the social ladder and the tone in the letter remains very formal and polite. The lower standing of Dent shows when he wants to dedicate an article to Airy with the following line; ‘to G.B. Airy, by his obedient and humble servant, E.J. Dent.’

Dent and Airy were to know each other for years and worked together closely. One would think that there would some equality or friendship after all these years. But this was not the case. Airy was higher up on the social ladder and the tone in the letter remains very formal and polite. The lower standing of Dent shows when he wants to dedicate an article to Airy with the following line; ‘to G.B. Airy, by his obedient and humble servant, E.J. Dent.’

And the respect that Dent has for Airy’s ability is shown in a comment that Dent writes to professor Plana in Italy; ‘The mechanical world lost a genius when Airy was appointed Astronomer Royal.’

As written above Dent was specialized in chronometers and precision clocks. In this field workmanship, use of the right materials, technical inventions etc. all must lead to great accuracy. The work that is done is mostly of small dimensions.

Turret clocks on the other hand are large mechanism that keep time fairly well but up until 1840 couldn’t compare with their to a regulator. It was deemed almost impossible to get the this accurate because of the extreme conditions that influence a turret clock.

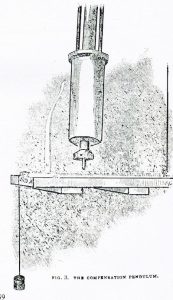

First there is the influence of temperature changes that are strong in a tower. With temperature changes metal expands or contracts which influences for instance the length of a pendulum and with that the rate of a clock. Secondly there is the wind that works on the hands, pulling or pushing, sometimes even blocking the movement all together. To counter this, the movement is driven by a large weight load which pushes through the wind influence.

We know from a letter in 1842 that Dent didn’t want to be bothered about turret clocks at all. During a trip with twelve chronometers to measure the difference between two meridians he visits Whitehurst in Derby, a reputed maker of turret clocks. After a return visit in August Dent writes a letter to Whitehurst that all future requests about turret clocks will be directed to him without any commission.

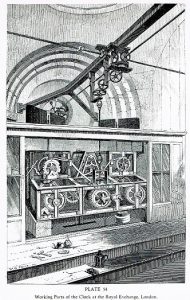

The clock for the Royal Exchange.

In October 1842 Dent meets the architect Tite at an exhibition of the escapement that Airy invented and he made. Tite was commissioned to build the new Royal Exchange after the fire of 1834 and tells Dent that he is thinking of placing a turret clock. Dent immediately tells him to ask Airy for consider Whitehurst and writes this to Whitehurst as well.

In October 1842 Dent meets the architect Tite at an exhibition of the escapement that Airy invented and he made. Tite was commissioned to build the new Royal Exchange after the fire of 1834 and tells Dent that he is thinking of placing a turret clock. Dent immediately tells him to ask Airy for consider Whitehurst and writes this to Whitehurst as well.

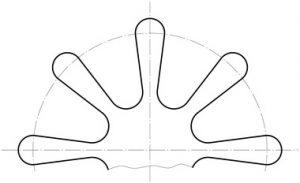

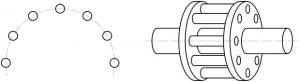

Here is a drawing of the escapement that Airy invented. The two wheels are connected by a small spring. The first wheel stops the wheel train and is pushed by it. The second wheel is pushed by the small spring and drives the pendulum. Thus giving a small and constant impulse to the pendulum which gives very good accuracy.

Here is a drawing of the escapement that Airy invented. The two wheels are connected by a small spring. The first wheel stops the wheel train and is pushed by it. The second wheel is pushed by the small spring and drives the pendulum. Thus giving a small and constant impulse to the pendulum which gives very good accuracy.

Probably on Dent’s advice Airy asks Whitehurst and Vulliamy (a London maker that also made turret clocks see picture on the left) to make a tender for the clock.

Probably on Dent’s advice Airy asks Whitehurst and Vulliamy (a London maker that also made turret clocks see picture on the left) to make a tender for the clock.

As stated before Dent wasn’t interested in turret clocks until this moment (april 1843). He even wrote to Airy that the turret clock production was very much behind technically in comparison to chronometer- and regulator making. But between April and July something must have happened because when Dent returns from a trip to Paris in July he finds an invitation to make a tender for the clock of the Royal Exchange.

Since there are no documents we can only speculate what could have happened. Dent visited Airy often on Monday. Maybe during a conversation about the construction and specifications of this clock Airy asked; “Why don’t you make the clock?”.

We know that Dent was an enterprising man who looked for new opportunities. For instance he made an improved compass, aneroid barometer and a dipleidoscope. The last device was used for determining the exact moment of midday for the location where one was.

Dent might have seen an opportunity to get into turret clock making on a larger scale and using this clock as an advertisement.

Whitehurst also receives the invitation and makes a trip to London. He meets Tite who tells him Airy spoke highly of him. In a letter Whitehurst thanks Airy for his kind recommendation and might have thought that he almost surely would get the commission.

Around September 1843 Dent writes Whitehurst and tells him that he, Whitehurst and Vulliamy are the three who are in the running for the commission. And Dent is curious what kind of price Whitehurst will ask. Whitehurst is not amused! Dent promised him a few months back never to compete in the Turret clock business and now he is!.

Vaudrey Mercer the writer of my book suggests that Dent probably wanted to work together with Whitehurst. That Whitehurst would make all the large parts and that Dent would take care of the technical and precision work. I am not sure that this is the case. Dent had no experience yet with Turret clocks and maybe just hoped that Whitehurst would tell him. In any case, after this letter Whitehurst never answered or wanted to deal with Dent again.

Dent and Whitehurst both sent in their plans. Dent is the cheapest by far. We can only speculate why but there is a good chance that he did this because he saw the good publicity in the commission for future work.

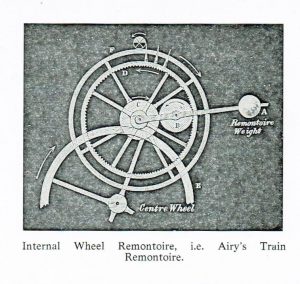

Dent gets the commission and gets to work straight away. He makes a trip to France and Belgium to look at turret clocks and turret clock factories. In Paris he gets the idea to use a remontoir in the going train. A remontoir is a system in a clock that winds a small weight or spring at short intervals to drive the escapement. In this way the escapement always gets the same impulse. But a second advantage is that the heavy weight that is needed to drive the hands does not work on the escapement and interfere too much with the pendulum.

The remontoir that is used in this clock was also invented by Airy and made by Dent. An arm carrying a weight is lifted every 15 seconds by the heavy weight of the clock, this arm drives the ‘scape wheel.

When clicking on the button below, you can see a video of a Wagner remontoire which works very similarly.

The clock becomes a technical marvel. It has a 2.2 m zinc and steel pendulum and a Graham deadbeat escapement. I will highlight a few other improvements.

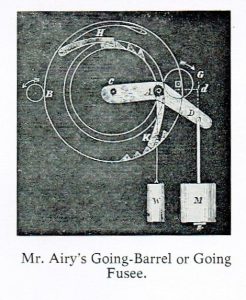

During the winding of a clock, the driving power (spring or weight) does not drive the clock. This can result in loss of rate. But it can also damage the clock because when the ‘scape wheel is not turning, an anchor pallet can land on the tip of a tooth of the ‘scape wheel. In a normal chronometer or regulator usually Harrison’s maintaining power is used. When the clock is wound an auxiliary spring is engaged which then drives the train. But with a turret clock being driven by a weight in excess of 100 kgs this is very difficult because a spring that heavy wouldn’t have the right flexibility. Airy comes up with a fairly simple but effective construction that comprises of an auxiliary weight that automatically drives the clock when it is being wound.

During the winding of a clock, the driving power (spring or weight) does not drive the clock. This can result in loss of rate. But it can also damage the clock because when the ‘scape wheel is not turning, an anchor pallet can land on the tip of a tooth of the ‘scape wheel. In a normal chronometer or regulator usually Harrison’s maintaining power is used. When the clock is wound an auxiliary spring is engaged which then drives the train. But with a turret clock being driven by a weight in excess of 100 kgs this is very difficult because a spring that heavy wouldn’t have the right flexibility. Airy comes up with a fairly simple but effective construction that comprises of an auxiliary weight that automatically drives the clock when it is being wound.

From the correspondence we learn that Dent is concerned about making of the pinions. Because of the size of the pinions the cooling down creates tension between the sections that easily can result is cracks. The outer part being already cooler than the centre which will contract after that when cooling down. He first thinks of cast iron with a brass mantle. But later lets go of that idea because he is weary of the mantle wearing down.

In the end he settles for lantern pinions which are not often used by English clockmakers. But they have very little friction and do not collect dirt like the usual bayleaf shaped pinions. (see below)

But since Dent buys his own large lathes for cutting wheels and pinions he again looks into the shape of the wheel teeth. This time able to make them himself. He starts a correspondence with several scientist and experiments for months. Finally he comes up with epicycloid curved teeth and hypocycloid curved teeth. Shapes that are still used in gear boxes today which need to be able to withstand great and very constant force.

But since Dent buys his own large lathes for cutting wheels and pinions he again looks into the shape of the wheel teeth. This time able to make them himself. He starts a correspondence with several scientist and experiments for months. Finally he comes up with epicycloid curved teeth and hypocycloid curved teeth. Shapes that are still used in gear boxes today which need to be able to withstand great and very constant force.

There are many letters in which the daily problems show. There is a letter for instance in which he asks Airy for help. Tite is complaining to Dent that he is using ordinary brass instead of bell brass (bronze) for the wheels which is cheaper. But Dent argues that the brass that he uses is being hammered by two men for a day which is actually more expensive but that Tite just doesn’t want to listen.

Another cause for a lot of frustration are the bells which were not made by Dent but by the firm of Mears. There are a lot of letters that illustrate the problems. There is a letter in August 1844 in which Dent complains to Mears to send more than one man next time because the bells are much too heavy for one person. In another letter to Airy he complains that because of the work on the bells rubble had fallen in the clock room but gladly the movement had not been installed yet. Another letter in August lets us know that Dent is frustrated because after several days of work there were only three bells hanging!

The clock ran well but the chimes and bells remained a headache for a long time. Dent complains to Airy that Professor Taylor who was the composer of the quarter chime and musical melody doesn’t seem to understand the difference between the melody and chimes. The quarter barrel has only a diameter of one foot, while the musical barrel has a diameter of 3 feet!

But the most problems are still the bells. A number of bells is out of tune. In December Dent complains that the workmen have worked a whole day to hang the large bell, but that this bell needs to be removed the next day to fit another smaller bell.

The problems with the bells remain until 1852 and give a lot of ammunition for Dent’s critics in 1844 and 1845. There is even an anonymous pamphlet that circled in London criticising Airy for being not a horologist and Dent a chronometer maker and not knowing anything about turret clocks. The pamphlet was probably written by Vulliamy or Whitehurst who didn’t leave a chance unused to criticise Dent and Airy being helped by the failing striking of the clock.

The second part about the realisation of the Great clock of the Houses of Parliament will follow later.