The Queen’s Clock part 3, the ‘table clock’ and circa date.

The table clock

In Holland the invention of the pendulum by Huygens in 1656 lead to the development of the ‘Hague’ clock. In England this invention lead among others to the originating of the table- or bracket clock as was the name for the type until some fifteen years ago. There is a number of distinct characteristics that often occurs with this type of clock. For instance the dial is made of brass and matted in the center. On this dial a silvered chapter ring is mounted. The hands are foliate pierced and made of blued steel. The wooden case has a square or rectangular body surmounted by a cushion or bell-shaped top. The front – and back door have glass panels while the sides usually have pierced frets. The movements are heavily executed and consist of vertical brass plates connected by pillars. These movements are driven by spring barrels in combination with a fusee and have a duration of eight days. Finally one can state that until the end of the eighteenth Century table clocks had a verge escapement in combination with a pendulum.

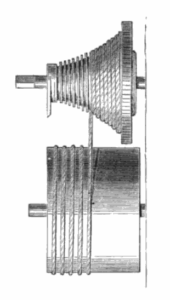

The fusee

Without becoming too technical I think it is useful to explain about the fusee, one of the characteristic components of the movement of the English table clock. Basically it is a conically shaped axis with a groove for the chain or gut line to run into. This chain or gut line is connected to the spring barrel. When winding the barrel via the fusee, the chain or gut will be wound around it. The force that a spring barrel it exerts on the movement diminishes when it unwinds. The change in force of the spring barrel is not good for the accuracy of the movement. But because a fully wound spring will only work on the narrow part of the fusee it has only little leverage. With the spring running down and becoming less powerful it works more and more on a wider part of the fusee gaining leverage. In this way the difference in force of the spring is mitigated which enhances the precision of the movement.

Engeland

English clockmakers coming over to Holland introduced the table clock around 1675. At first this type of clock isn’t produced or copied very much. The ‘Hague clock’ remains the dominant spring driven clock during the seventeenth Century. At the beginning of the eighteenth Century the production of these Hague clocks starts to decline. Maybe this is a result of the increasing numbers of table clocks made by Dutch makers and the import of these clocks from England. Still the production of Dutch table clock remains relatively small. The Dutch and English traditions logically have a lot in common, not in the least because of imported parts from England to Holland. But still there are some differences between the two. below I will cover some of the most distinct.

Dutch striking

Usually English clocks only strike on the hour. When there is more elaborate striking it is usually quarter chiming. It consists of a melody that sounding each quarter and becoming longer at each following quarter. At the (full) hour in addition to the quarter melody, the hours will be struck. One might think of the striking of Big Ben.

With Dutch half hour striking the hour will sound on a large bell. At the half hour the clock will strike the number of the coming hour on a small bell (higher pitch). It might sound a little odd for an English person but this has to do with the way the Dutch name the half hour. At 6.30 a Dutch person will say (roughly translated) ‘the half hour of seven’. This is similar to German. Since the Dutch say ‘the half hour of Seven’ it is logical that the clock will strike seven times.

There is also a Dutch quarter striking which goes as following. The striking of the hour and half hour is identical with Dutch half hour striking. But the first and third quarter are indicated by a single strike on the alternating large and small bell. This Dutch quarter striking is uncommon for table clocks but is quite usual for longcase clocks and Zaanse wall clocks.

Calendar and moonphase

Calendar and moonphase

Most English clocks and especially those made in London only have date indication.. More elaborate calendar indications are far more common with Dutch clocks, like day of the week and month. Moonphase indication is also very common with Dutch clocks. In my opinion this has to do with high- and low tide which are caused by the gravity of the moon. This was very useful in country this close to sea level. For instance sea ships only could get close to Amsterdam with high tide.

Alarm

Table- and longcase clocks made for the English (London) market hardly ever are equipped with an alarm, those are usually fitted in wall clocks. With Dutch clocks alarms are much more common. Even the large longcase clocks often have one. Dutch table clocks or English table clocks for the Dutch market often have alarm work. I do need to state that alarm work is less common than i.e. Dutch striking.

The chapter ring

There are some differences in the execution of the chapter ring although there are some Dutch clocks that don’t show these. But these characteristics are almost never visible on English clocks.

The outer rim is calibrated for every five minutes. (5-10-15-etc) With English clocks the numbers 20 until 40 are upside down. With Dutch clocks these numbers are turned so they are straight up. Another feature of the minute calibration are the five-minute arches. Between the five minute numbering, the calibrated ring has arches. This is a feature that is seen often on Dutch clocks from the middle of the 18th Century on.

English export clocks for the Dutch market often have one or more of these characteristics.

A circa date for our clock

In a short article like this it is not possible to discuss all exceptions. But is general I can state that the table clock doesn’t change a lot between 1680 and 1780. The main shape of the case remains the same and doesn’t seem to be affected by big changes stylistically. These changes are apparent in the execution of the applied ornaments and for instance the engraving of the back plates of the movements. A reason for this could be the sample books that were used by the workmen.

Because of these subtle changes to details only it is not easy for a layman to date a table clock. I will try to explain how we establish a circa date for our clock by looking at these details.

Looking for clues

Ebony

Our clock is veneered with ebony which unfortunately does not give us useful information for establishing a date. During the whole period of table clock production ebony or ebonized wood was used. True ebony which was very rare and expensive was used mostly in the 17th Century after which the cheaper ebonized wood was mostly used. The process of ebonizing consisted of veneering a clock with pearwood which was then stained black. True ebony was scarcely used in the 18th Century for expensive and more exclusive clocks. Besides ebony (and ebonized) other types of wood were used to veneer clocks. These different types of wood are typical for certain periods. Walnut or burr walnut is used in the first half of the 18th Century while mahogany is the typical wood for the period 1760 – 1800.

The inverted bell top

Because the top part of the case changes during the course of the development of the bracket clock, the different appearances can be useful for a (pro-ante) date. Our clock is surmounted by an ‘inverted bell top’ which was introduced around 1715. It consists of convex part surmounted by a concave part. Basically this is the other way around when we look at a bell which would have a concave part surmounted by a convex part (true bell). The inverted bell top remains into use until the end of the 18th Century. Around the middle of the 18th Century the ‘true bell top’ is introduced which becomes the type most used in the second half of the 18th Century. Because of the long use of the inverted bell top it gives a date between 1715 and 1800.

Herm and trailing flower mounts

Herm and trailing flower mounts

On the canted corners of the case of our clock there are applied cast mounts. Often these consist of a head or half figure with flowers and foliage below. The Herm- or Caryatid mounts come into use around 1735 and are used until the end of the 18th Century on some of the table clocks.

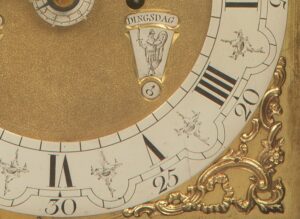

The dial

The dial consists of several parts like the brass plate itself, the applied chapter ring and the spandrels. (corner ornaments) As stated before, these part all went through changes that can give us clues for dating the clock. The dial is depicted here in its unrestored condition.

First there is the arched shape of the brass plate. The ‘arched dial’ followed the square dial. It seems the clockmakers switched from the square dial to the arched dial in a relative short period between 1710 – 1715. After that hardly any table clocks with square dials were made. At first the arches were narrow but after a decade or so these would take up almost the full width of the dials. The ‘arch’ was probably popular because it provided space for extra dials, a moonphase or a large signature plaque. It also made the clocks higher and more impressive looking. Our clock has a moonphase (typically Dutch) which is lined with a sector inscribed the with the tunes for the tune selection.

Another somewhat more subtle characteristic are the protective rings that are around the two upper winding holes. These were very common often in a more larger execution with earlier clocks until the end of the first quarter of the 18th Century. After then, they become smaller and are used less and less. Around 1750 the use of these rings seems to have vanished altogether.

Finally there is the aperture for the mock pendulum. This is a small disc connected to the pendulum and moves in the arched slot under XII showing the clock is running. The mock pendulum is a feature seen on table clock from the early beginning on. The use becomes in disuse in the course of the third quarter of the 18th Century.

The Chapter ring

Looking at the chapter ring we see that the five-minute indication is done in the ‘Dutch way’ with the numerals between 20 and 40 straight up instead of upside down. The outer ring calibrated for the minutes is still straight which seems to indicate a date of origin before 1750. More difficult to explain but an important indication is the letter type. With our clock the letters and numerals (of the minute indication) are relatively large and squarish. In my opinion this is something seen often with clocks between 1730 and 1750.

The spandrels

The brass ornaments which fill the corners around the chapter ring are called spandrels. These corner ornaments go through a distinctive development through time giving evidence for dating a dial. The spandrels on our dial are a variation of the so-called ‘mask-spandrels’. These come into use after the ‘crown and cherub’ spandrels around 1720. The term refers to the face or mask that is placed in symmetrical foliate ornament. A distinctive difference with the earlier ‘crown and cherub’ spandrels is that the mask spandrels fill the whole space of the corner outside the chapter ring leaving no un-decorated space. These are also flatter having much less relief than earlier spandrels. Our mask spandrels are a little version having a bit more relief and of a slightly more open form. (1730-1740) Around 1750 the ‘rococo spandrels’ become into use. These are asymmetrical foliate spandrels that are more open of form leaving more empty space.

Taking everything into account I think that our clock was made between 1735 and 1745.