The stylistic development of the Dutch longcase clock, part 1.

In November 2015 I held a lecture on the stylistic development of Dutch longcase clocks. Dutch in this case is not the whole of modern The Netherlands but only ‘the seven provinces’ with both South and North Holland the most important. A stylistic development of these clocks is not yet described in the literature on these clocks. This blog will give a general picture on the subject and of course will lack exceptions and fine nuances.

The invention of the longcase clock.

To start the history of the Dutch longcase clock one needs to go to England first, because there lays its origins.

I know that the word ‘invention’ is bold in an article like this. But when we now think of longcase clocks, there is an arche type which comes to mind it has a base, a trunk and a hood with a glass paneled door which houses the dial. For instance in the fairy tale ‘the Wolf and the seven goats’, the clock looks ike that. But before 1658 this shape did not exist. It was the English clockmaker Ahasuerus Fromanteel who invented this form. It would become the standard form more or less for over 250 years! The brass dial with appied chapter ring would also be used for a very long time.

The clocks were very practical because they stood independently and housed the weights in the trunk. But most of all the clocks were attractive and soon (well to do) many wanted a clock like this in their interior.

The clocks were also revolutionary in an other way. They housed movements that were being regulated by a pendulum. At the start of the 17th already Galileo Galilei discovered that it is the length of a pendulum that determines the frequency and not the sieze of the arc. It was the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens who developed a movement that was regulated by a pendulum together with Coster in 1657. It is hard to imagine today how important this invention was because clocks with pendulums are so common. But before the use of the pendulum clocks were regulated by a balance or foliot. But these were very inaccurate and clocks often were off 15 minutes a day. But the pendulum made it easily possible to regulate a clock so it wouldn’t be off more than a minute!

It seems astonishing that Fromanteel already knew of this invention in 1658; it was a Dutch invention and it had a sort of patent on it. But Fromanteel was of Flemish descent and we know that he went to the Dutch church. So in all probability he spoke Dutch. A contract still excists in the archives of The Hague between Coster and Fromanteel . One of Fromanteel’s sons is to go into tuition with Coster and taught the invention of the pendulum and Fromanteel of course pays for this. The first longcase clocks had a verge and short pendulum like the ‘Hague Clocks’ of Coster.

The anchor escapement and second’s pendulum.

The next important development in the story on longcase clocks comes around 1669-1670 when William Clement invents the anchor escapement. It had a number of advantages. It was easier to make because of the omission of a bevel gear. It also made it easy to fit the movement with a seconds beating pendulum and with that a seconds hand. Allo ne had to do was to lengthen the escapement arbour through the dial and fit a seconds hand onto it. This clock by Clement has the same three elements as Fromanteel’s clock. The base, trunk with door and hood. But now the dial has a seconds hand and the cherubs are not engraved but applied spandrels. The clocks wih their classical pediments are of the architectural style. This style will not be followed in Holland.

The first Dutch longcase clocks.

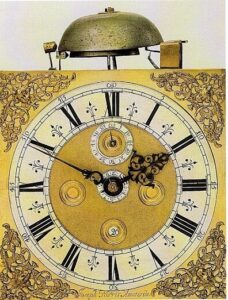

Only around 1675 the first Dutch longcase clock was introduced by an English clockmaker Joseph Norris. The similarities with the English examples are evident. There is the matted dial with silvered chapter ring and cherub spandrels. But on the other hand there are differences typical for Holland. These were probably done because of the Dutch taste and needs.

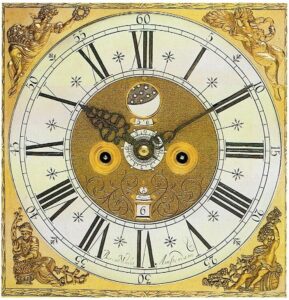

When we look at the movement we see two bells fort he so-called Dutch half hour striking. Most English clocks only strike the hours. If there is a more elaborate striking, it are usually all the quarters that are struck.But the Dutch clocks strike the hours on a large bel land the half hours on a small bell fort he coming hour. In Dutch 1.30 is ‘half 2’, in being half way the 2nd hour. And not adding the half hour tot he hour before. There is also an alarm fitted tot he movement which can be identified by the alarm disc at the centre of the hands. Furthermore there is a moonphase and calenderwork. To my opinion Dutch customers liked moonphases indications because tide is related to the position of the moon. For travel and trade this was very important because with high tide, ships could get closer to harbours and depart more easily. On London clocks there is hardly ever more than a date indication.

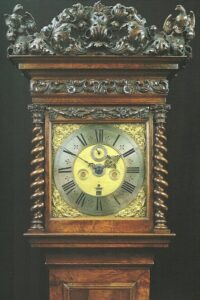

There are also clear differences to the cases when compared with their English examples. There is fine foliate carving to the door, hood and most of all as cresting. Further the hood has twisted columns that resemble the columns on the large baroque cupboards. There is also a lenticle (glazed aperture in the door) which shows the movement of the pendlum bob. There are English clocks with lenticles but these are rare and mostly on clocks from the 1690 – 1710 period.

The next clock that I use as an example (made circa 1685) again shows typical Dutch features. This clock was made by Ahasuerus II and John Fromanteel sons of the earlier mentioned Ahasuerus Fromanteel. They opened up an Amsterdam branch of their ‘multi national’ company. Below the hands we see small apertures for calendarwork (days of the week and date). The movement has again an alarm and Dutch striking.

Appearantly these clocks were in demand because after some time Dutch clockmakers also started to make longcase clocks.

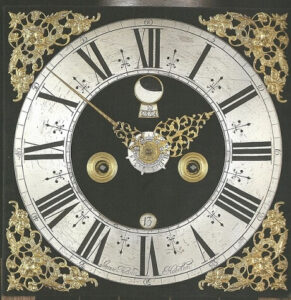

One of the first longcase clocks of a Dutch maker is this clock by Jacob Hasius made around 1690, about 30 years after the first longcase clock in England. The first striking feature is the velvet covered dial which is customery with ‘The Hague clocks’. The large triangular foliate pierced hour hand is also a feature often seen with contemporary Hague clocks. This dial also shows a nice example of a moonphase with these early longcase clocks.

The next clock shown is again made by the Fromanteel brothers around 1695-1700. This fine ebony clock has a duration of one month. There is no extra calendar work to this clock only date but it does have Dutch striking and an alarm. Most striking is that this clock now made by English makers has a velvet covered dial and the triangular pierced hour had mentioned above. One can conclude that these makers of English origin were open to Dutch influence and customs in Dutch clockmaking.

Although the [picture is a little small, it is clear that there is carving to the hood and lenticle. This makes it very likely that this clock had a carved cresting which is now lacking.

The next clock is by the Dutch maker Pieter Klock of Amsterdam made around 1700. Clearly the case doesn’t have carved ornament like the clocks before. It is a more sober, less ornate type of case. These cases appear around 1700 and for a little while these clocks were made together with the more ornate ones. This type of case probably fitted better with a certain kind of clients and also in the furniture art we see a less ornate style appearing. Another striking feature is the moulded cresting with three ornamental urns. This is called the dome top. With these the clocks become highter a trend that will increase in time.

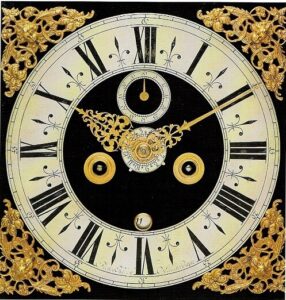

This is the dial of the Wallis clock. Around this time the brass dials become in favour of the velvet covered dials. Again typical for Holland are the moonphase and calendar (date, day of the week) and the alarm. A new feature are the season spandrels. For the first time in about 35 years there the cherub is replaced. The man in front of a fire is of course Winter. Bacchus on a wine drum with grapes is autumn (wine harvest). A lady with scythe and corn sheaf is spring. A last the lady with a wreath and basket of plenty is summer.

At this moment in time around the end of the 17th C when the less adourned cases are in fashion, English and Dutch loncase clocks look a lot alike. But there are clear differences. One of the most obvious is in the door of the trunk. First the Dutch door protrudes about 1.5 cm from the case and lays ‘on top’ of the plane. The doors on the English clocks are level with the frame around it. A second difference is the moulding surrounding the door. The Dutch clocks have a fine ogee moulding. The English clocks have a more plain half circle moulding.

When finding a Dutch movement in a case with a non-protruding door and a half circle moulding may well indicate a marriage between the Dutch movement and an English case.

Wordt vervolgd.